A Rebuttal: Hope Anderson's article - “The Wife”: Glenn Close’s Oscar Bait, Built on Literary Lies

A historian should know better.

Am I actually, giving a scathing rebuttal to a Wordpress blog published in 2018? Do I really have nothing better to do with my time?

Yes to the first question.

Also, yes to the second question. But I make poor decisions with my time constantly, this shouldn’t be a surprise. I have very little impulse control.

The other night my mother and I were talking about the issue of women who have the credit for their work taken by men, which drifted into a discussion of men who take credit specifically for the work of their wives. For instance, the famous legal battle between Margaret Keane and her husband, Walter, who had sold her famous paintings as his own work for years before she demanded credit.

This reminded my mother of the film “The Wife” starring Glenn Close, based on the 2003 novel by Meg Wolitzer. Mom had watched the movie, I had not and still have not, but this isn’t a movie review so that hardly matters. Talking about the movie, in typical ADHD fashion, led to looking it up online to see if it was based on a specific true story or just on the general history of men taking credit for the work of women.

This rabbit hole brought us to this blog article from 2018

I could probably have let this go (I am capable of accepting that some people just have wrong opinions and letting it go…sometimes, occasionally…if you are here from my TikTok account then you are probably calling bullshit, but I don’t care. You don’t know me.)** except that I looked at the bio page of the author and saw this:

Hope Anderson…[earned her] BA Magna cum Laude at Wellesley College, where she won the History prize, she pursued graduate studies in Japanese History at the University of California, Berkeley - Bio

She’s a historian and a historian should have known better to write that garbage. So now I’m left yelling into the void of the internet about a blog post from 6 years ago.

Now you’re all caught up, let’s start.

Let’s start with the simple fact that it is settled history (as settled as history can get anyway) that men steal the work of women and take credit for it. It’s happened for literally all of recorded history. Big things like Rosalind Franklin and DNA all the way to small things like Mark* taking credit for the report that Stephanie actually put together and when Stephanie complains she’s told she’s not being a “team player” and it “doesn’t matter who gets the credit” except that Mark is clearly going to get the promotion based on this and Stephanie will get passed over…again.

Or as Dolly puts it:

Working nine to five, what a way to make a livin'

Barely gettin' by, it's all takin' and no givin'

They just use your mind and you never get the credit

It's enough to drive you crazy if you let it

And luckily Hope Anderson isn’t trying to claim that doesn’t happen (at least explicitly) so we can skip past that discussion and move right to her argument that this isn’t a factor in the world of literature.

Read the full article if you like, but I’ll just address a few bits of it here.

Unfortunately, it occurs in a so-so movie built on a false premise: that Joan, whose literary brilliance is already in evidence during her undergraduate years at Smith in the late 1950’s, must choose between failure as a woman writer and success as her husband’s ghostwriter.

The first major problem is unilaterally calling this a false premise. Whether it happened in the 1950s commonly or not, we know that male writers taking credit for their wive’s work is a thing.

Hope, I think Zelda Fitzgerald, Colette, Margaret Steffin, and Florence Deeks (among others) might like to have a word with you on the idea that this is a “false premise.”

Critics who are unacquainted with the period could simply search online for American women writers of the 1950’s and find Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, Patricia Highsmith and Mary McCarthy, for starters. Or they could look at the Wikipedia page on 20th century American women writers, which has nearly four thousand entries. But apparently no one has bothered, so it falls to me.

No one is claiming women were never published. No one is claiming that women didn’t, on occasion, become incredibly famous for their writing. What we are saying is that women had to fight twice as hard (maybe even harder) than men did for that same acclaim.

Consider this from Shirley Jackson (who traumatized entire generations with the story The Lottery, so she’s definitely famous) in her own autobiography.

In her memoir, Life Among the Savages, Jackson wrote about going to the hospital to deliver her third child, and having the following exchange with the receptionist:

“Occupation?”

“Writer,” I said.

“Housewife,” she said.

“Writer,” I said.

“I'll just put down housewife,” she said

But more importantly, let’s just look at the number of best-selling authors by gender from over the years, based on the New York Times best sellers list.

Women have almost never hit the gender equality line on this graph, but they don’t even come close to hitting it in the 30 years that Joan Castleman’s character would have been ghostwriting for her husband.

But let’s also look at the main conflict that really sets this story off. Joan Castleman’s husband is about to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Would Joan have won that award if she’d published under her own name?

Well it’s not impossible, women have won the Nobel for literature before. However, women have only won 14.28% of all Nobel Prizes in Literature.

By the time of Joan’s husband winning (we don’t know the exact year, but Joan has been apparently ghost-writing for him for 30 years, so let’s just say late 1980s) only 6 women would have won the prize in literature. So while it’s true that women were being published, it’s also true that it was more difficult to gain acclaim and fame as a female author.

Which brings us to my next annoyance with Anderson’s argument.

Recently Smith had graduated a literary star: Sylvia Plath, class of ’55, who was a nationally published writer of short stories and poetry at twenty, won a Fulbright and earned a graduate degree at Cambridge. Guess who was back at Smith teaching in 1958? Plath, who no doubt would have taught Joan Castleman if Joan weren’t fictitious. With her slew of prizes, publications and fellowships, Sylvia Plath would have been a much better role model for Joan than Elaine Mozell (Elizabeth McGovern), the film’s lady writer, who tells Joan that even if she’s published she’ll never be read, so why bother?

While it is true that by the time Plath was teaching at Smith (when Castleman was fictionally attending), she had won numerous awards and prizes and fellowships, it is also true that Plath was still not achieving great fame at the time. Most of her fame and sales of her work came after she took her own life in 1963. In fact, her own Pulitzer prize in poetry was awarded posthumously for work that was published after her death.

All of which makes her a really poor example to use when critiquing the premise of this story, saying “well Joan Castleman should have known she could succeed because Sylvia Plath did” ignores the very dark and unfortunate history of how Plath reached the fame she eventually did.

To finalize my rebuttal, let’s return to this sentence from earlier in the article.

Or they could look at the Wikipedia page on 20th century American women writers, which has nearly four thousand entries. But apparently no one has bothered, so it falls to me.

First of all, a historian saying “they could look at the Wikipedia page” is already a red flag.

But let’s maybe take her advice. Let’s look at the number of female writers in the 20th century.

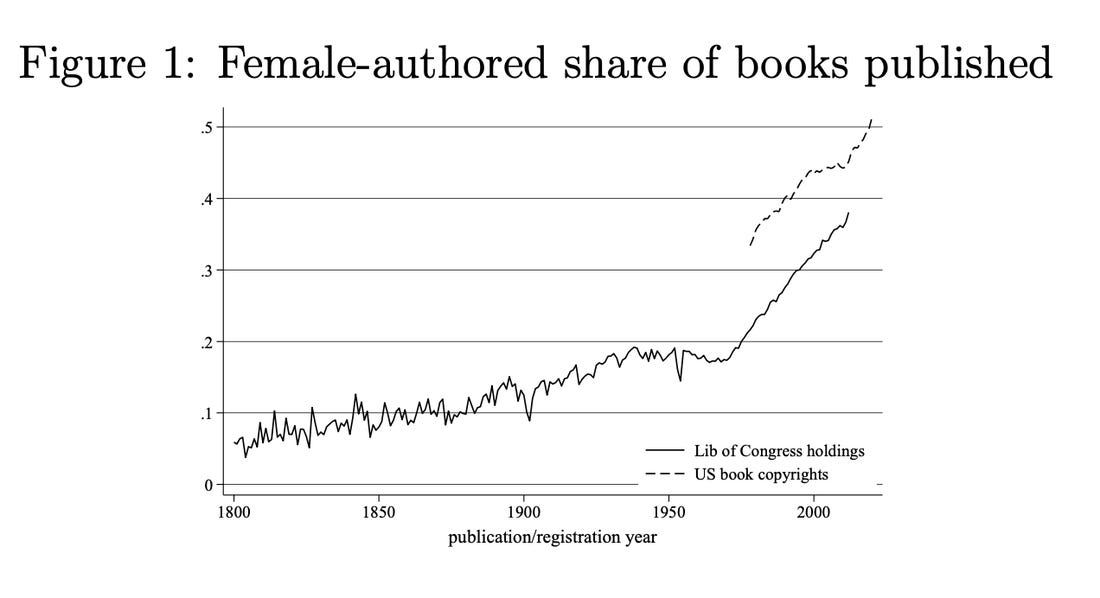

Hmm, curious…it’s almost like women prior to the 1970s were extremely underrepresented as published authors.

Joel Waldfogel, an economist at the University of Minnesota's Carlson School of Management, conducted a study recently (so yes, Anderson wouldn’t have access to this in 2018, but this is hardly the first study of this type) and his analysis of female writers found that:

between roughly 1800 and 1900, the share of female authors hovered around only 10 percent each year.

In the 20th century, female authorship began to slowly pick up. By the late 1960s, the annual percentage of female authors had grown to almost 20 percent.

It isn’t until the 1970s, nearly 2 decades past when Joan Castleman would have begun ghostwriting for her husband, that women begin to break the glass ceiling of publishing.**

The idea that Joan is forced by sexism into thirty years of fraudulent literary servitude is so absurd that even Glenn Close’s bravura performance can’t redeem it.

“The Wife”: Glenn Close’s Oscar Bait, Built on Literary Lies

But is it, Hope? Is it really?

But ignoring the history, let’s simply consider the fact that sexism is still a well-known factor in traditional publishing (as is racism).

In traditional publishing, female authors’ titles command nearly half (45%) the price of male authors’ and are underrepresented in more prestigious genres, and books are published by publishing houses, which determined whose books get published, subject classification, and retail price.

Comparing gender discrimination and inequality in indie and traditional publishing

Women also tend to have their work miscategorized and shelved as YA (especially if they write in genres like Science Fiction and Fantasy) or passed off derogatorily as “chick-lit” simply because the author is female.

Women have long used male pseudonyms to get published, from George Elliot to J.K. Rowling (the irony of this with that author in particular is not lost on me) but that hasn’t changed.

In 2015, the author Catherine Nichols decided to do a little experiment to see if the publishing world really was as gender biased as the figures suggested. Firstly, she sent her novel to 50 agents using her own name and received just two manuscript requests. But when she sent the same material to the same agents, using a male pseudonym, the novel was requested 17 times.

“He is eight and a half times better than me at writing the same book,” wrote Nichols. “My novel wasn’t the problem, it was me – Catherine.”

So Hope Anderson, not only is it not absurd that a woman in the 1950s might have faced an extreme uphill battle to become an acclaimed, Nobel prize-winning author, it is not absurd to think that women might still face a tougher fight for that goal today in the 21st century.

Or as one of the literary greats of the 21st century put it:

I’m so sick of running as fast as I can

Wonderin' if I'd get there quicker if I was a man

*We’ve all met a Mark. We all hate Mark. If your name is Mark and you don’t do this, I apologize for using your name, but look…get over it.

**Who are we kidding? I’m basically this comic in human form:

***This is, not coincidentally, also when birth control becomes a common thing and women begin entering the workforce (and college) in higher numbers as well.