Life of a Showgirl: Glitter, Grind, and the Performance of Femininity

Pardon me while philosophize another Taylor Swift album

Like many women, for me this October 3rd meant two things.

A day to rewatch Mean Girls, obviously.

But most importantly it was the day, the hour, the moment of the release of Taylor Swift’s most recent album.

The Life of a Showgirl

As it turns out, the title was ironic.

The title suggests glitz, sequins, and Vegas glamour — feathers in the hair, champagne flutes in hand, and women shimmering beneath hot lights. Instead, the songs unfold as a meditation on labor, commodification, and what it means to live your life as a perpetual performance. The showgirl, Swift makes clear, is not an emblem of effortless luxury but a working woman whose beauty is a job, whose body is a stage, and whose private self is always up for consumption.

The album’s final track spells it out through the fictional story of Kitty, a chorus-line dancer chewed up by fame:

“She said, “I’d sell my soul to have a taste of a magnificent life that’s all mine”

But that’s not what showgirls get…They ripped me off like false lashes / And then threw me away…Who wish I’d hurry up and die/But I’m immortal now, baby dolls/I couldn’t if I tried

The showgirl survives, but not unscathed. She is immortalized in sequins and photographs, but only at the cost of her humanity. It’s the central metaphor of the record — and a lens through which to see the longer history of femininity as performance.

The Long History of Performing Femininity

The idea that womanhood itself is a kind of theater runs deep. Across cultures and centuries, femininity has been scripted, costumed, and policed as if it were a role in a play.

Medieval Europe made this explicit in the case of Joan of Arc. Her “crime” was not only leading French troops but also wearing men’s clothes — a literal costume violation treated as heresy. Appearance, not action, became the ground for her execution.

Early modern etiquette manuals instructed women on how to smile, walk, and gesture, laying out a choreography of virtue that blurred the line between sincerity and performance. Even in the 19th century, the “Cult of True Womanhood” in America taught that femininity meant piety, purity, domesticity, and submissiveness. Every woman was expected to act the part, whether she believed in it or not.

By the 20th century, mass media amplified the stage. Hollywood glamour queens like Marilyn Monroe embodied femininity as performance — platinum hair, breathy voice, diamonds on display — even as Monroe herself felt consumed by the role. The political sphere was no better: women who entered public life found themselves judged as if they were contestants in a beauty pageant. Hillary Clinton crafted her pantsuit uniform as armor after early ridicule involving a questionable photo shot by press, while AOC’s lipstick and clothes are dissected as if they reveal more about her politics than her policies ever could. A single Instagram post in red lipstick sparks as much commentary as her committee speeches — proof that women in politics are judged as performers on a stage, not simply as lawmakers.

Swift channels this legacy in Eldest Daughter, skewering the relentless scrutiny of digital culture:

“Everybody’s so punk on the internet / Every joke’s just trolling and memes / Everybody’s cutthroat in the comments / Every single hot take is cold as ice.”

The tools may have changed — from inquisitorial courts to Twitter threads — but the script is the same. Women are still judged not only for what they say or do but for how they perform femininity.

Showgirls in History: Spectacle as Survival

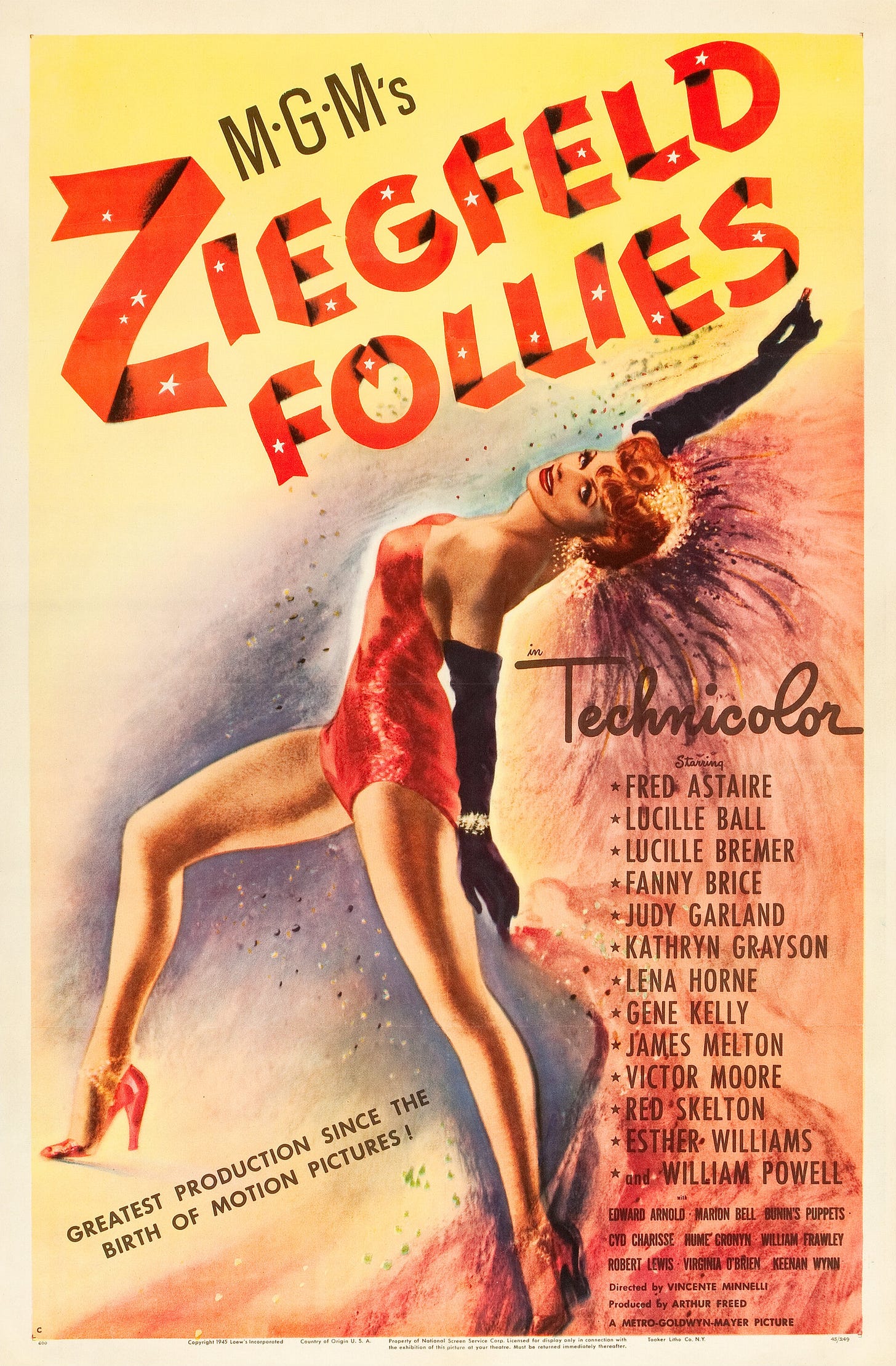

The literal showgirl emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a highly visible figure of modern entertainment. Ziegfeld Follies dancers in New York, Folies Bergère performers in Paris, and Las Vegas chorus lines in the mid-century all sold the image of effortless beauty. But behind the feathers and sequins was grueling labor: endless rehearsals, strict weight and appearance requirements, exploitation by managers, and little job security.

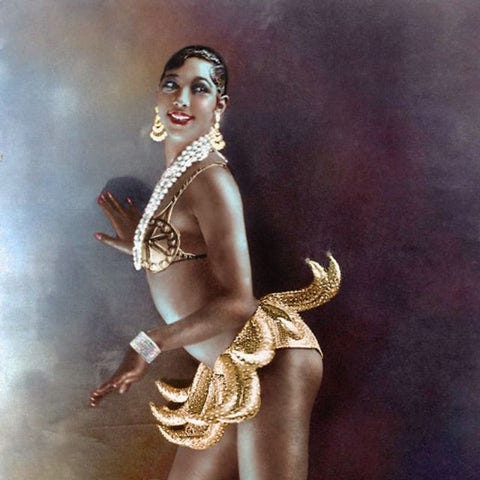

Josephine Baker, one of the most famous dancers of the 1920s, understood this paradox. Her banana-skirt performances both catered to and exaggerated racist, colonialist fantasies. By turning the caricature up to eleven, she mocked it — while also making herself indispensable to Parisian nightlife. Later, she used her fame to smuggle intelligence for the French Resistance and to speak out against segregation in the U.S. Baker’s stage persona was a performance of femininity, race, and exoticism — but one she bent into power.

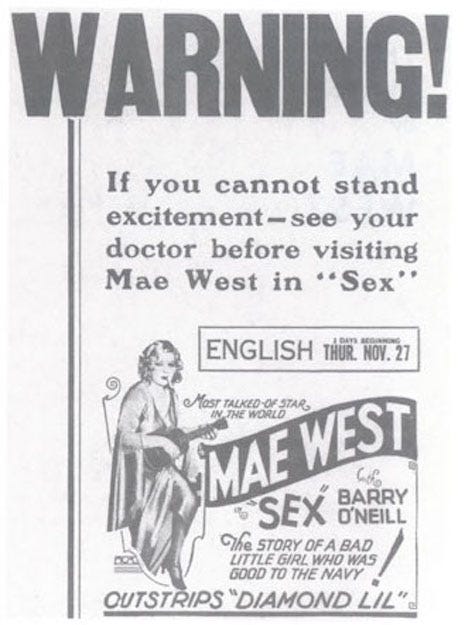

Mae West did something similar in Hollywood. Arrested multiple times for “indecency” in her Broadway years, she built a persona of sexual wit and command. Her bawdy one-liners scandalized the censors but delighted audiences. Crucially, West wrote much of her own dialogue, securing creative authority unusual for women at the time. She accepted the role of spectacle, but she authored it, too.

Swift’s Life of a Showgirl acknowledges this lineage. Like Baker and West, she makes visible the double bind of spectacle: it can empower, but it also consumes.

Swift’s Ironic Showgirl

Swift takes the archetype and injects irony. Unlike Baker and West, she is not just bending the system; she owns it. By 2025 she was a billionaire artist, having reclaimed her masters and designed tours that booster entire local economies. She is both the act and the executive, the woman in sequins and the one counting receipts.

But the lyrics refuse to romanticize this power. In Father Figure, Swift mocks the patronizing executives who once controlled her career:

“I can make deals with the devil because my dick’s bigger … You pulled the wrong trigger / This empire belongs to me.”

It’s a declaration of independence, but one that still frames power in the language of exploitation. Even at the top, the showgirl remains defined by the structures she’s had to fight through.

And in the title track, she refuses to let the glitter obscure the pain:

“Pain hidden by the lipstick and lace / Sequins are forever.”

The sequins endure. The women do not.

Everyday Showgirls

Swift’s metaphor resonates because it isn’t confined to celebrity. Women in all walks of life are asked to perform versions of the “showgirl life.”

Honey explores how even simple endearments like “sweetheart” or “lovely” become weapons of condescension — unless spoken with sincerity:

“When anyone called me ‘Sweetheart’ / It was passive-aggressive at the bar … And I cried the whole way home … But you touched my face, redefined all of those blues.”

It’s not about stadium lights but about the micro-performances demanded every day: the smile at work, the careful choice of outfit, the balancing act of being approachable without being “too much.”

In Wi$h Li$t, she contrasts the spectacle others demand with her own ordinary dreams:

“They want those bright lights and Balenci’ shades … I just want you … We tell the world to leave us the fuck alone, and they do / Got me dreaming ’bout a driveway with a basketball hoop.”

It’s a rejection of the fantasy, an embrace of the mundane as liberation.

Even her sharpest satire, like Cancelled!, reflects the gendered dynamics of reputation:

“Good thing I like my friends cancelled … At least you know exactly who your friends are / They’re the ones with matching scars.”

Here the “showgirl” is anyone who has lived under public judgment, scapegoated and then discarded.

Curtain Call

The lights come up and the sequins sparkle, but what The Life of a Showgirl really reveals is what happens when the audience goes home. The bruises under the tights, the silence after the ovation, the exhaustion of being immortalized while still expected to smile.

Swift doesn’t let us leave with the fantasy intact. She lingers on the lipstick that hides pain, the bouquet of flowers handed at the stage door, the way applause can feel like a cage as much as a crown. What makes her version different is that she refuses to disappear when the curtain falls. Where so many women in history were discarded once the performance ended, she insists on returning to the stage on her own terms — not just the act but the author, the producer, the one who decides when the show is over.

The irony of The Life of a Showgirl is that it is both the spectacle and the unmasking of spectacle. It’s sequins and shadows, lipstick and labor, applause and ache. And maybe that’s the point: not that women can finally step out of the spotlight, but that someone has learned how to use it without being swallowed whole.

Because the show was always going to go on. The question was never whether women would be asked to perform — it was who would finally get paid for it.

this is a great piece, and love the concept of your substack! "unmasking of a spectacle" is a great way to put it, and I feel like TTPD's ICDIWABH serves that purpose better than this album, although I did enjoy it.

Fantastic review, one that thinks, quotes, listens, propounds. Thank you.