Inconceivable: A Field Guide to the Worst Men You’ve Ever Met

How The Princess Bride Predicted the Manosphere

One of the funniest things about The Princess Bride is that it is a fairy tale, a parody, a romance, and an adventure all at once.1 One of the truest things about it is that it nails a certain kind of man so precisely you can practically hear a podcast microphone powering on in the distance.

The film came out in 1987. The internet as we know it did not exist. There was no algorithm handing sad guys a conveyor belt of grievance content at 2 a.m. There was no “debate me” livestream economy. And yet the villains in this story map eerily well onto the modern ecosystem of men who are convinced the world has wronged them because women will not behave like vending machines that dispense validation on command.

This is not me saying “everyone who’s ever complained about dating is Prince Humperdinck.” Sometimes people are lonely. Sometimes people are awkward. Sometimes the modern world is genuinely isolating and brutal.

I’m talking about a specific type. The guy who thinks his feelings are evidence. The guy who thinks he’s oppressed when really he’s just entitled. The guy who believes women’s autonomy is an affront, not a fact. The guy whose personality is basically “I was promised a prize and I demand to speak to the manager.”

Let’s go villain by villain.

Humperdinck: entitlement with a crown

Prince Humperdinck is the purest distillation of “I deserve you” energy. He does not love Buttercup. He selects her. He collects her. He treats her like proof that he is the kind of man who gets whatever he wants.2

That is the first and loudest overlap with modern men’s rights jerk stereotypes: the belief that women are a resource. That women’s bodies and attention are part of a social contract that has been unfairly revoked. That the world is broken because women have choices now.

Humperdinck’s masculinity is not competence, bravery, or leadership. It’s ownership. He wants a wife the way he wants a kingdom: as something that certifies his status. He doesn’t have to like her. She just has to be his. His anger isn’t heartbreak. It’s rage at the idea that a woman can say no and mean it.

He is also the perfect example of how “nice” is often a costume for control. Humperdinck can do polite. He can do ceremony. He can do “I’m a respectable prince.” But the politeness is conditional. It lasts exactly as long as Buttercup plays her assigned role.

The minute she doesn’t, he drops the mask. And that, historically and currently, is the tell. The villain isn’t the man who is awkward. The villain is the man whose kindness evaporates when you stop cooperating.

How to spot them in the wild:

The “nice guy” date who is charming until you say no, then instantly pivots to “you’re stuck up / you’re going to die alone / women only want jerks.” (Civility is conditional.)

The workplace prince who expects women to do emotional/admin labor because it’s “natural” (take notes, plan birthdays, smooth conflicts), and gets punitive when you don’t.

The “traditional values” guy who frames control as protection: “I just don’t want you dressing like that / going there / having male friends,” and calls it love.

The “marriage as status upgrade” dude who wants a partner as proof he’s winning life, not as a person with interiority.

Count Rugen: the grievance bureaucrat

If Humperdinck is entitlement, Count Rugen is the part that gets colder.

Rugen is not driven by romance. He’s driven by sociopathy. His whole deal is cruelty as proof of intellect. Torture as a science project. Pain as a way to feel important.

This is the archetype of the man who takes his internal emptiness and turns it into a philosophy. The guy who insists his cruelty is rational. The guy who frames empathy as weakness. The guy who thinks being detached makes him smarter, when it really just makes him dangerous.

Rugen also embodies the institutional version of misogynistic logic: harm without mess, harm without passion, harm that can be filed away and defended. He doesn’t need to scream. He has mechanisms. He has tools. He has a job title. He represents the kind of violence that thrives in systems because it can hide behind “procedure,” “research,” “just doing my work.”

He’s the dark future of grievance culture. Not the guy ranting online. The guy who turns that rant into policy, into punishment, into “experiments,” into rules that hurt people while pretending it’s neutral.

How to spot them in the wild:

The “I’m just being objective” manager who frames discriminatory outcomes as meritocracy: “We can’t lower standards,” when the “standards” are vibe-based and selectively enforced.

The pseudo-science guy who cites “biology” to justify hierarchy (women are “naturally” X, men are “naturally” Y), as if a Wikipedia skim equals expertise.

The procedural sadist in bureaucracies who makes you jump through endless hoops because the point is control, not resolution.

Vizzini: “logic and facts” as a dominance performance

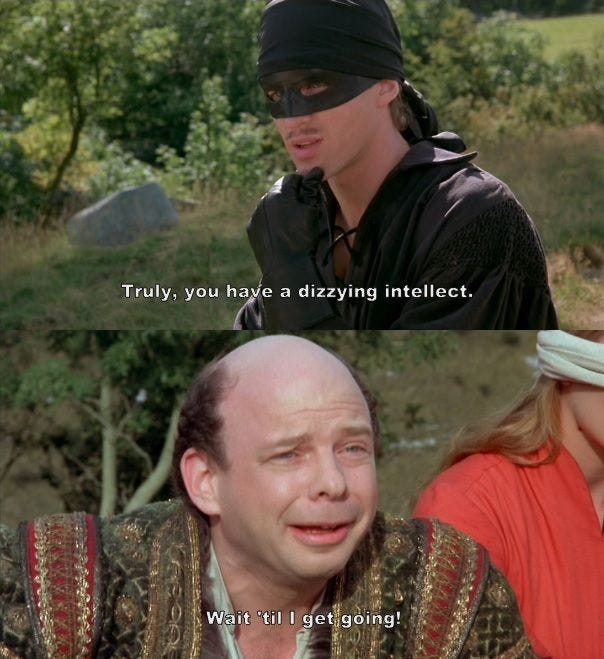

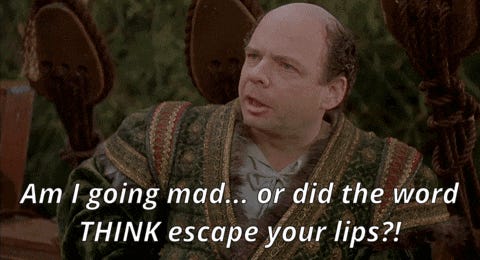

And then there’s Vizzini, who feels like he was built in a lab to haunt comment sections.

Vizzini’s greatest weapon is not intelligence. It’s the performance of intelligence. He talks constantly. He announces his brilliance. He treats everyone around him as an audience. His goal is not to understand reality, but to win the social hierarchy game.

This is the archetype of the guy who thinks “debate” is a substitute for character. The guy who uses wordiness as intimidation. The guy whose confidence is inversely proportional to his competence. The guy who believes that if he can talk fast enough, nobody will notice he’s fundamentally full of it.

Modern grievance spaces are full of this type: men who claim they are being oppressed while loudly controlling the conversation, men who treat any disagreement as “emotional” while they have a full tantrum in paragraph form, men who call themselves logical while their logic is just a pile of assumptions held together by ego.

Vizzini is also a perfect illustration of how these guys use other men. He does not see Fezzik and Inigo as friends, partners, or humans with inner lives. He sees them as assets. Muscle and skill he can rent. He thinks he is entitled to loyalty because he is “the smart one.” It is the same way a lot of modern jerks treat women, too: people exist to be useful, not to be respected.

How to spot them in the wild:

The debate bro friend-of-a-friend who turns your lived experience into a cross-examination: “Define ‘harassment.’ Cite a study. Prove intent.”

The “devil’s advocate” guy who only advocates for the devil when women talk.

The comment-section lecturer who replies to feelings with “facts,” then writes a 900-word tantrum about how calm and rational he is.

The pickup-artist adjacent chatterbox who treats social interaction like a hackable system and women like puzzles, not people. (Optimizing, “negging,” “high value/low value” language.)

The unifying thread: women’s autonomy as an insult

Here’s the connecting tissue between all three villains. They are furious at the idea that other people have agency.

Humperdinck is furious that Buttercup isn’t grateful to be chosen. Rugen is furious that someone might survive him, resist him, or deny him the satisfaction of control. Vizzini is furious that the world will not submit to his narrative of superiority.

This is why the film’s villainy still reads clean. The story isn’t just saying “these men are mean.” It’s saying “these men believe their desires are law.” That belief is the root of a lot of modern misogynistic grievance politics. It’s not always loud. Sometimes it’s dressed up as fairness. Sometimes it hides behind pseudo-science. Sometimes it comes with a smirk and a “just asking questions.” But it’s the same move: “My disappointment is your fault, and I am justified in punishing you for it.”

Why the film still feels satisfying

A lot of modern media softens villains to make them “complex,” which can be interesting, but it can also blur the line between harm and charisma. The Princess Bride does not do that. It lets villains be villains. It refuses to romanticize entitlement. It refuses to dress cruelty up as woundedness that begs you to empathize with and fix it.

And then it contrasts them with a different version of masculinity. Westley doesn’t need ownership to feel like a man.3 Inigo doesn’t need dominance to be worthy. Fezzik doesn’t need cruelty to be strong. The villains are not “men.” They are a particular kind of man. The kind built out of ego, grievance, and control.

Which is why it remains such a useful little cultural lesson.

If someone tells you they want love but what they really want is compliance, that’s Humperdinck.

If someone tells you cruelty is reason and empathy is stupidity, that’s Rugen.

If someone tells you you’re too emotional while they do a TED Talk about why they’re entitled to the world, that’s Vizzini.

Inconceivable, right. And yet.

Did I really write TWO Princess Bride themed articles this week?

And in truth he doesn’t even want her as a status symbol. Just a beautiful symbol of purity he can use to get the war he wants for…some reason?

I acknowledge that his little temper tantrum about her marrying Humperdinck is a little close to the line of him feeling entitled to her and owning her affection, but…let me have this.