“As You Wish": In Which Love Is More Than Romance

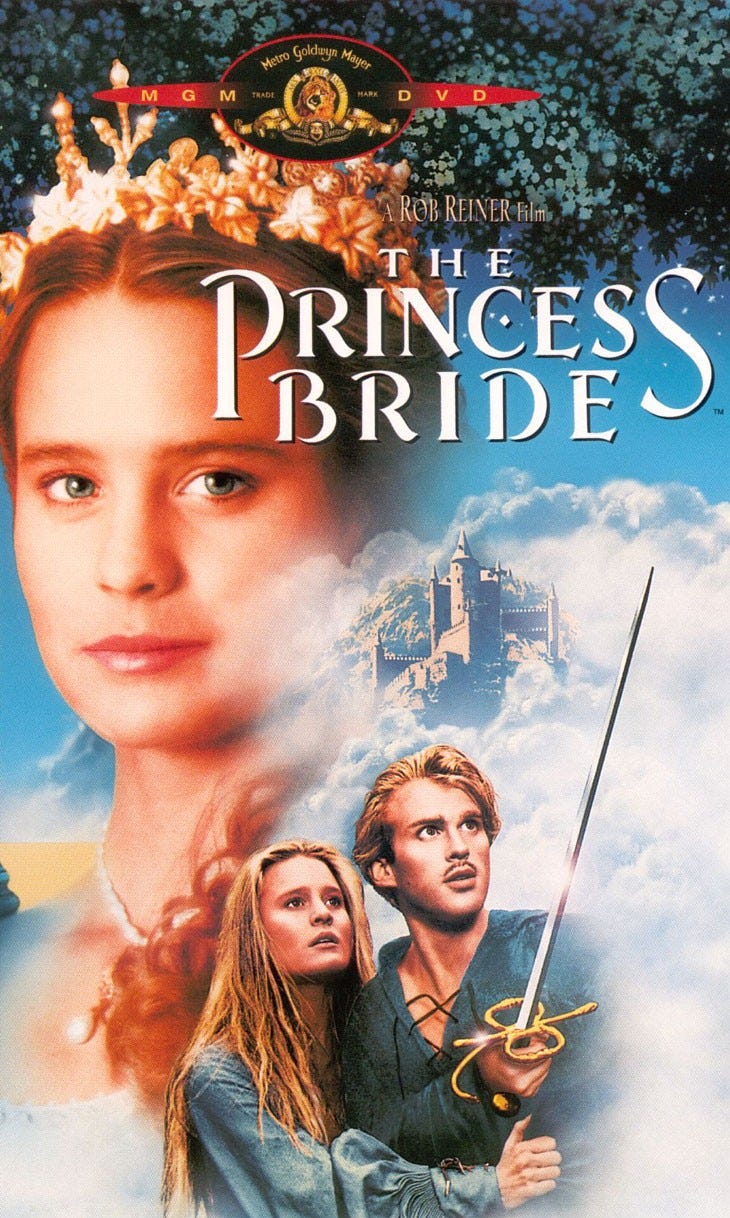

The Many Loves Inside The Princess Bride

My first exposure to The Princess Bride was not in a cool, film-bro way. It was in the most elementary-school-girl way possible: it showed up as a birthday present.

It was my first slumber party, one of the early social events that can make or break a young girl’s popularity. A dozen girls, all sugar-charged and giddy with the thrill of illusory freedom, piled into the den in a mess of sleeping bags and friendship politics. By the end of the night, at least three girls had cried, I knew at least two girls would be lifelong enemies1, but all of us had enjoyed the movie.

I don’t remember who gave me the movie. Probably my parents. Might have been my eldest sibling, which would honestly be the only truly nice thing they ever did for me. Having a narcissistic sibling twelve years older than you makes for an…interesting childhood. But even if it wasn’t them, I like the idea that it could have been. That this story arrived the way stories sometimes do: imperfectly delivered, possibly by someone who doesn’t deserve credit, and still offering you something you needed.

So I unwrapped the gift and my parents approved it as a late night film for a group of 8 and 92 year olds.3 Someone put the DVD in and the movie started and for the next hour and a half we got to live inside a world where adults were ridiculous, sword fights were theatrical, and love was treated like something real and tangible and not just about romance.

The Princess Bride is one of those rare comfort movies that doesn’t require you to turn your brain off to love it. You can come back to it as an adult, with all your gender-studies instincts fully activated, and it still works. Not because it’s flawless. It’s because it’s gentle in a very particular way. It refuses the modern reflex where being in on the joke turns into contempt for the story. It’s playful, but it’s not sneering. It’s earnest without being embarrassed about it.

But coming back to it as an adult does make you look at the characters differently. There is a certain contingent that sneers at the film, and Buttercup in particular. She’s seen as whiny, useless, hysterical; accused of being “the weak link,” when she’s actually one of the clearest illustrations of what it means to live inside the restraining reality of patriarchy as a woman.

Buttercup is not written as a woman with a wide menu of options. She’s written as a woman whose life is treated like a diplomatic resource. She’s “the most beautiful woman in the world” the way oil is “the most valuable resource in the world.” She is useful. She is desired. She is argued over. Her consent is not the center of the conversation, it’s the obstacle.

In that kind of world, Buttercup’s behavior is not evidence that she’s foolish or unable to act for herself. It’s evidence that she understands the stakes. She bargains. She bluffs. She tests people to see if they are safe. She tries to leverage the only power she has been told she possesses, which is her value as an object everyone else wants. That’s not liberation, obviously. But it is a survival strategy. It is a woman doing calculus under patriarchy and getting blamed for the fact that the math is ugly.

The tragedy isn’t that she’s dramatic. The tragedy is that the world keeps forcing her into situations where “dramatic” is a reasonable response.

And then the film does something that, frankly, a lot of modern romances don’t. It gives us villains who are not romanticized.

Prince Humperdink is not secretly wounded, not misunderstood, not the kind of villain you’re supposed to find sexy because he has cheekbones and a title. He is entitlement with a crown. He treats Buttercup like an acquisition and the kingdom like a toy set. His masculinity isn’t strength, it’s ownership. He’s the guy who thinks being “a prince” means the world should rearrange itself to accommodate his desires. And what makes him frightening isn’t that he’s charming. It’s that he isn’t. He’s bland, petulant, and violent. The horror is the banality.

Count Rugen is the cruelty the story refuses to soften. He is sociopathy in a velvet jacket. He doesn’t do violence in a passionate, messy way. He does it clinically, as a project, as a hobby, as an ego exercise. His whole vibe is “I can do this because I have status and no one will stop me and I get off on it.” He is a reminder that systems don’t need monsters. They just need men who believe they’re entitled to other people’s bodies.

And Vizzini? Vizzini is a different kind of villain, but he belongs in the same ecosystem. He’s not the state. He’s not the aristocracy. He’s the guy who thinks intelligence is dominance. He talks nonstop, he performs brilliance, he treats people around him like props in his mental theater. He is the kind of man who thinks being the smartest person in the room means nobody else is fully human. He’s funny, sure. But he’s also a perfect little caricature of how ego disguises itself as intellect.

And that brings me to what the movie does with masculinity when it isn’t villainous.

Because one of the reasons this film still feels like emotional comfort instead of a nostalgia trap is that it gives us men who don’t have to prove themselves through humiliation. Westley wins by competence and restraint, not by domination. Inigo is driven by revenge, yes, but he is also tender, loyal, and openly emotional without being punished for it. Fezzik is gentle strength in human form. His softness isn’t a joke. It’s part of why he’s lovable.

Their friendship is one of the most quietly radical relationships in the film. Fezzik and Inigo choose each other. They take care of each other. They show up. They have that rare dynamic where a bond is allowed to be affectionate and devoted without being undercut by “no homo” panic or mockery. When Inigo is at his lowest, Fezzik doesn’t fix him by shaming him into manhood. He nurtures him back to himself. That is love. Not romantic love, but love nonetheless.

Yes, there’s Buttercup and Westley, the fairy-tale center of gravity. But the story’s real magic is that “true love” isn’t treated like a single romantic currency that only matters if you’re a man and a woman on a hilltop.

The film keeps expanding the definition. The grandfather reading to the grandson is true love. It’s care work. It’s patience. It’s showing up for a kid who’s sick and cranky and insisting he hates romance, and saying, gently, I know what you think you hate. Let me give you the good parts. Let me stay with you until you remember you can still believe in something.

Fezzik and Inigo’s friendship is true love. The kind that doesn’t demand you perform. The kind that keeps you alive long enough to finish your story. Even Westley’s devotion is framed less as possession and more as persistence, the commitment to return, to endure, to keep a promise when it would be easier to give up and move on.4

And then there’s Miracle Max and Valerie, which is its own miniature essay on power dynamics in relationships.

Valerie clearly runs that household. She calls him out, she sets boundaries, she drags him back toward decency when he wants to wallow in resentment. She’s practical, grounded, and completely unimpressed by his ego. She is also, importantly, not punished for it. The movie doesn’t treat her authority as a joke at Max’s expense.

And Max, despite being a snarky jerk with a victim complex and the energy of a man who has never once considered therapy, values her. He listens to her. He needs her. He loves her. Their dynamic isn’t “nagging wife, henpecked husband.” It’s “older woman with a spine keeps her bitter genius of a partner tethered to humanity.”

The film lets them be funny without making Valerie small. She matters. She’s the reason the scene works. She’s the reason Max shows up at all. Without her the story ends in tragedy. Westley dead, Inigo’s revenge foiled, Buttercup strangled on her wedding night to fuel a petty man’s warmongering.

Which brings me back to why this movie felt so good at that first sleepover, even if I couldn’t name it.

It gave us a fairy tale where the villains are clearly villains, not romanticized as misunderstood.5 It gave us a heroine trapped in a rigid system and it let us see her not as stupid, but as surviving. It gave us men who could be soft and loyal and emotionally rich without making that softness a punchline. And it treated love as something bigger than romance: something you do, something you choose, something you practice. Something that can be a relationship, a friendship, a caregiving act, a promise kept.

So yes, we can critique it. We should. But we can also hold onto what it offers. A story that says the world can be cruel, and systems can be coercive, and men with power can be terrifyingly ordinary. And still: people can choose tenderness. People can choose loyalty. People can choose the good parts.

In Memoriam: Rob Reiner and Michele Singer Reiner

Rob Reiner helped give us The Princess Bride, a film that has stayed in people’s lives not just because it’s quotable, but because it’s kind.

He is mourned alongside his wife, Michele Singer Reiner. In the wake of their deaths, it feels fitting to return to the storybook frame that makes The Princess Bride more than an adventure. It’s a film about love as something passed along, reread, and shared. A reminder that stories can be an inheritance.

They were the worst. Maybe not lifelong enemies worst, but at that age “lifelong” doesn’t feel that long. Just imagine pint size Regina George and you’ll get the picture.

Had to have been that birthday, because the gift was a DVD version of the film and that came out the year I turned 9. DON’T DO THE MATH ON THAT. I’M OLD. I’VE ACCEPTED IT.

If you are one of the girls from that party or one of their parents, I’m pretty sure my mom is still embarrassed about the “I want my father back, you son of bitch” line being in a movie she approved for a elementary school age sleep over, but…mistakes happen.

Should he have maybe sent a letter at some point in those five years? Admittedly yes. Communication solves a lot of problems, Westley.

I can only take so many villain redemption arcs before villains lose all sense of urgency. Make villains villainous again, I say.