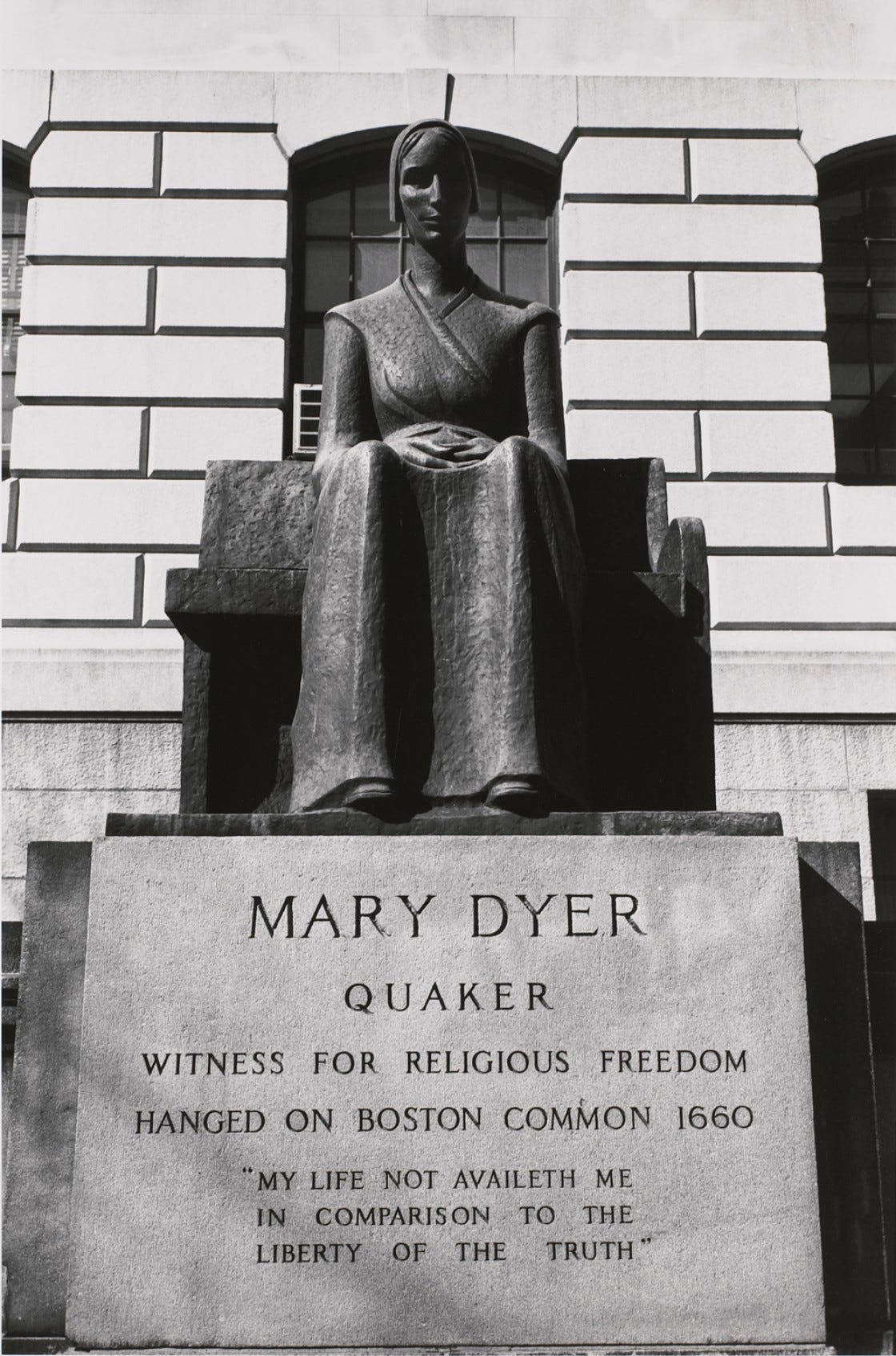

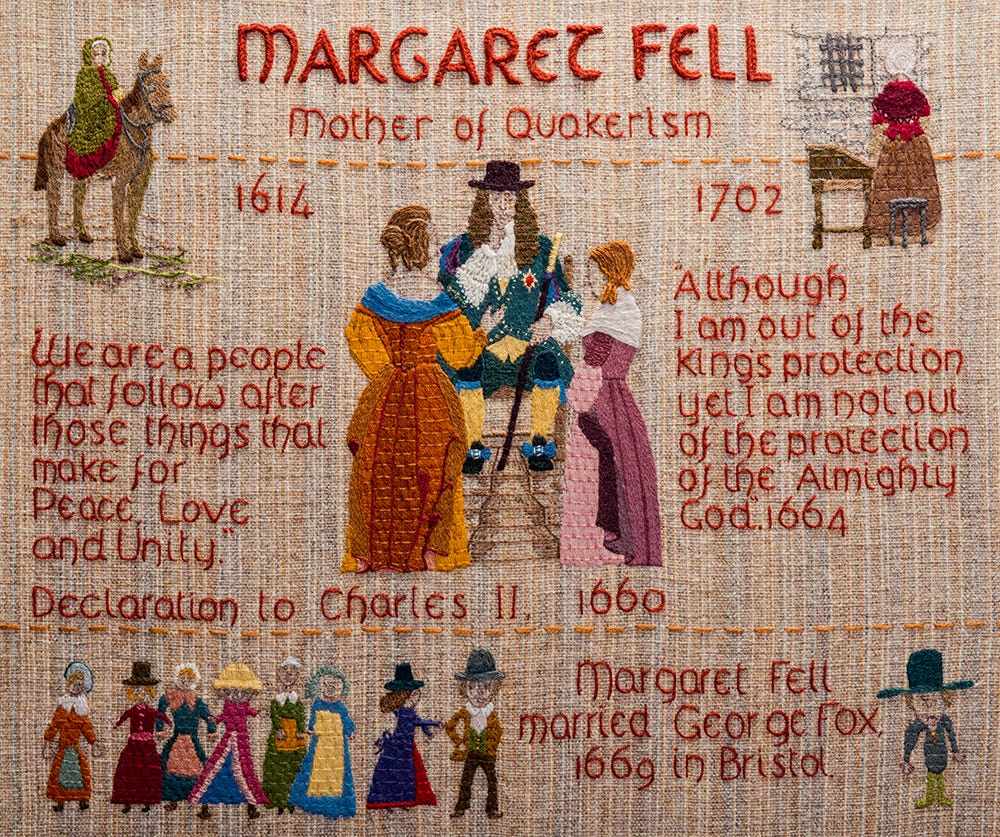

In this episode, I start with a guy in my YouTube comments insisting I “teach feminism, not history” and then take him on a little field trip to 17th-century Boston. Quaker women like Margaret Fell and Mary Dyer weren’t marching under a “feminist” banner, but they were doing something genuinely explosive for their time: preaching, publishing, and claiming spiritual authority in public while female. We’ll look at the theology that made that possible, the Puritan panic that tried to shut it down, and the long afterlives of these “disorderly” women in everything from suffrage to modern church fights over women in the pulpit. If you’ve ever been told that bringing patriarchy into women’s history is “too political,” this one’s for you.

Sources & additional reading

On Quaker women, preaching, and authority

Amanda E. Herbert, “Companions in Preaching and Suffering: Itinerant Female Quakers in the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World,” Early American Studies 9, no. 1 (2011).

Mary Maples Dunn, “Saints and Sisters: Congregational and Quaker Women in the Early Colonial Period,” originally in American Quarterly 30, no. 5 (1978), reprinted in Women in American Religion, ed. Janet Wilson James.

Jean R. Soderlund, “Women’s Authority in Pennsylvania and New Jersey Quaker Meetings, 1680–1760,” William and Mary Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1987).

M. D. Speizman and Jane C. Kronick, “A Seventeenth-Century Quaker Women’s Declaration,” Signs 1, no. 1 (1975).

Judith Rose, “Prophesying Daughters: Testimony, Censorship, and Literacy among Early Quaker Women,” Critical Survey 14, no. 1 (2002).

Gerda Lerner, “Women’s Rights in American History” (1971) – classic essay on why you literally can’t do women’s history without talking about feminism and patriarchy.

On Margaret Fell, women’s preaching, and feminist theology

Margaret Fell, Women’s Speaking Justified (1666). Modern-English editions and online annotated versions are widely available.

Phyllis Mack, Visionary Women: Ecstatic Prophecy in Seventeenth-Century England (University of California Press, 1992).

On Mary Dyer, Boston, and the politics of memory

Antonia Myles, “From Monster to Martyr: Re-Presenting Mary Dyer” (2001) – on how Dyer’s image shifts from dangerous heretic to safe Protestant heroine.

Stella Setka, “A Picture of Piety: The Remaking of Mary Dyer as a True Woman in Arthur’s Home Magazine,” American Periodicals 24, no. 1 (2014).